Joint cracking during exercise is a common occurrence known medically as crepitus, a term used to describe popping, cracking, or grinding sounds coming from a joint during movement. In most cases, this happens because of changes in pressure within the joint fluid or minor tendon movement over bone, not because something is breaking down. It’s similar to air bubbles forming and collapsing in a sealed system—noticeable, but often harmless.

Joint cracking that happens during physical activity is reported by more than half of adults at some point, according to clinical observations, especially during stretching, squatting, or strength training. It becomes more frequent with age and is commonly associated with factors like reduced synovial fluid lubrication, mild cartilage wear, or temporary muscle tightness. People who are starting a new workout routine or returning after inactivity tend to notice it more.

During exercise, when joints repeatedly crack or pop and start to raise concern, context matters. Crepitus without pain, swelling, or loss of motion is usually considered benign, while cracking combined with discomfort may point to conditions such as early osteoarthritis or tendon irritation. Understanding what causes these sounds and when they signal a problem helps set the stage for safer movement and smarter decisions about joint care.

Why It Happens

During exercise, joints experience changes in pressure, alignment, and muscular tension. One frequent mechanism behind exercise-related cracking is cavitation, where gas bubbles form and collapse within synovial fluid as the joint surfaces separate and reapproximate during motion.

Additional contributors include tendons or ligaments gliding over bony landmarks during repeated movement, especially in the knee and ankle joints. Muscle fatigue, temporary biomechanical imbalance, or limited flexibility can accentuate these sounds during activities such as squatting or cycling.

Exercise Effects

Exercise itself plays a critical role in joint health. Properly dosed mechanical loading improves synovial fluid distribution, enhances cartilage nutrition, and strengthens the muscles that stabilize joints. When cracking occurs without pain during exercise, it is generally not a contraindication to continued physical activity.

In contrast, excessive volume, poor movement patterns, or inadequate recovery may increase joint stress. Repetitive high-load exercises performed with improper technique can aggravate preexisting cartilage wear, particularly in the patellofemoral joint of the knee.

Normal vs Problem

Exercise-related joint cracking is considered normal when it is painless, consistent, and not accompanied by swelling, locking, instability, or reduced performance. Many individuals experience knee cracking during squats or cycling that does not progress or interfere with training.

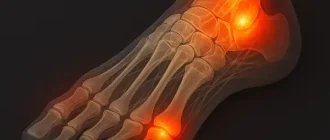

Cracking becomes clinically concerning when exercise provokes pain, joint swelling, stiffness after activity, or a sense of mechanical catching. These features may indicate conditions such as chondromalacia patellae, early osteoarthritis, tendinopathy, or meniscal pathology.

When to Avoid

Exercise should be modified or paused if joint cracking during training is accompanied by pain, visible swelling, warmth, or a sudden decrease in joint function. New-onset cracking following an injury or rapid increase in training intensity also warrants caution.

Ignoring these warning signs and continuing intense exercise may increase the risk of structural joint damage. Medical assessment is advisable before resuming full training loads.

Safe Training

To minimize joint stress, exercise programs should emphasize proper technique, controlled range of motion, and gradual progression. Low-impact activities such as cycling with correct seat height, resistance training with neutral alignment, and mobility-focused exercises are generally joint-friendly.

Strengthening the quadriceps, hamstrings, gluteal muscles, and calf muscles improves lower-extremity biomechanics and reduces abnormal joint loading. Adequate warm-up and recovery are essential components of safe training.

Medical Evaluation

Persistent or symptomatic joint cracking during exercise should be evaluated by a healthcare professional. Clinical assessment may include functional movement analysis, physical examination, and imaging studies such as X-ray or MRI when structural pathology is suspected.

Early identification of biomechanical or degenerative issues allows for targeted interventions, including physical therapy, technique correction, or individualized exercise modification.

Editorial Advice

Joint cracking during exercise is a common experience and, in most cases, reflects normal joint mechanics rather than disease. Exercise remains one of the most effective tools for preserving joint health when performed correctly and progressively.

Medical consultant Reyus Mammadli emphasizes that the key determinant is not the sound itself, but the presence of pain or functional limitation. When exercise-related cracking is painless and stable over time, continued physical activity is usually safe. If symptoms evolve, timely medical guidance helps ensure long-term joint protection.

References

Crepitus: Causes and Clinical Significance (clinical overview of joint sounds and mechanisms) — Mayo Clinic

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (knee biomechanics and exercise-related symptoms) — National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)

Physical Activity and Joint Health (evidence-based exercise guidance) — Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Knee and Ankle Symptoms During Exercise (sports medicine evaluation and red flags) — Cleveland Clinic

Joint Pain and When to See a Doctor (clinical decision guidance) — Johns Hopkins Medicine

Cartilage Health and Mechanical Loading (musculoskeletal health education) — National Library of Medicine (NCBI)

About the Author

Reyus Mammadli is the author of this health blog since 2008. With a background in medical and biotechnical devices, he has over 15 years of experience working with medical literature and expert guidelines from WHO, CDC, Mayo Clinic, and others. His goal is to present clear, accurate health information for everyday readers — not as a substitute for medical advice.