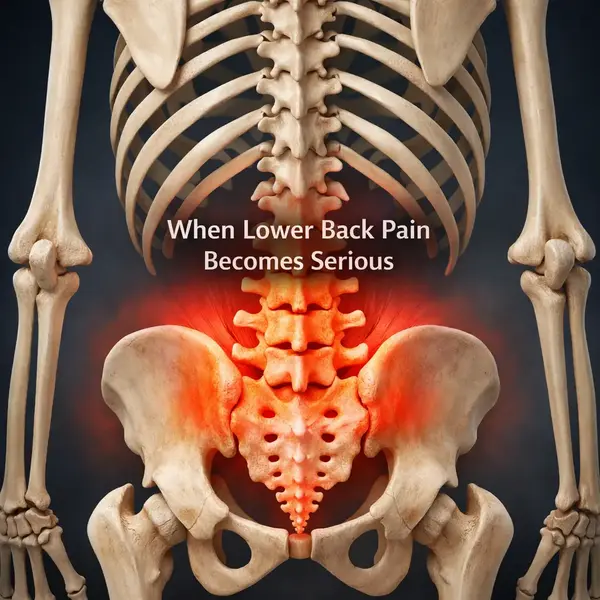

When lower back pain is serious, it usually means the discomfort goes beyond simple muscle fatigue or a temporary strain. Lower back pain refers to pain or stiffness in the area between the ribs and hips, and when it becomes severe or concerning, it often signals that more than everyday overuse is involved. It’s similar to a warning signal from the body, suggesting that something needs attention before the problem grows.

Lower back pain that turns serious enough to disrupt daily life affects millions of adults each year, particularly people over the age of 30 and those with sedentary routines or physically demanding jobs. Research shows that while most people experience lower back discomfort at some point, a smaller group develops persistent, intense, or potentially dangerous symptoms related to nerve irritation, spinal issues, or other underlying conditions. Factors such as aging, prior injuries, poor posture, and prolonged stress on the spine increase the likelihood that the pain becomes more severe.

After a long workday or upon waking, when recurring stiffness, sharp pain, or weakness in the lower back doesn’t improve, it can indicate a more serious issue. Learning how to recognize troubling symptoms, understand possible causes, and know when medical evaluation is necessary helps bring clarity and reassurance. This makes it worth taking a closer look at why lower back pain can become severe and what steps can help address it effectively.

Common Causes

Most lower back pain originates from mechanical or musculoskeletal issues. Muscle strains, ligament sprains, and minor disc irritation often develop after lifting something awkwardly, prolonged sitting, or sudden movement ⧉. In plain terms, the back is doing its job until it is asked to do too much, too fast — and then it complains, sometimes loudly.

Age-related changes are another frequent cause. Degenerative disc disease, facet joint arthritis, and mild spinal stenosis become more common after age 40, affecting nearly 30% of adults over 50 ⧉. These changes are often visible on imaging but do not always correlate with pain intensity, which surprises many patients.

Warning Signs

Certain symptoms suggest that lower back pain may be more serious. Pain that persists longer than 4–6 weeks, worsens at night, or does not improve with rest deserves medical evaluation. Neurological signs such as leg weakness, numbness, tingling, or difficulty walking raise additional concern.

Red flags also include unexplained weight loss, fever, or pain following trauma, especially in adults over 65. As Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, notes, persistent back pain combined with systemic symptoms should never be ignored — that is the body’s way of waving a very clear red flag ⧉.

Nerve Involvement

When lower back pain radiates down one or both legs, nerve compression is often involved. Conditions such as lumbar disc herniation or spinal stenosis can irritate the sciatic nerve, producing sharp, electric-like pain. This is commonly known as sciatica and affects about 10–15% of people with chronic lower back pain ⧉.

While many nerve-related cases improve without surgery, progressive weakness, foot drop, or loss of bowel or bladder control requires urgent care. These symptoms are uncommon, but when they appear, they mean business.

Diagnostic Tests

| Diagnostic Method | Accuracy & Key Nuances | Average US Cost |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray | 5/10 – Accurately shows fractures, alignment abnormalities, and advanced arthritis. Accuracy is limited because X-rays cannot visualize discs, nerves, or soft tissues. | $100–$400 |

| MRI | 9/10 – High accuracy due to excellent soft-tissue contrast, allowing clear visualization of discs, nerve roots, ligaments, and spinal cord. Particularly effective for identifying herniation, stenosis, and inflammation. | $1,000–$3,500 |

| CT Scan | 7/10 – Strong diagnostic value for complex bone anatomy and subtle fractures. Accuracy comes from high-resolution cross-sectional imaging, but nerve and disc detail is inferior to MRI. | $500–$3,000 |

| Physical Exam | 8/10 – Accuracy depends on clinician expertise and functional testing. Neurological assessment, gait analysis, and pain provocation maneuvers often identify clinically relevant pathology even when imaging is inconclusive. | $100–$300 |

X-rays are typically the first imaging test and are used to identify fractures, alignment issues, or severe arthritis. They are quick and widely available but do not show discs or nerves well.

MRI is the gold standard for evaluating discs, nerves, and soft tissues. It is commonly ordered when pain lasts longer than six weeks or when neurological symptoms are present.

CT scans provide detailed bone images and are often used when MRI is not possible. A thorough physical exam remains critical, as imaging findings must always be interpreted in clinical context.

Treatment Options

Conservative treatment is effective for most patients. This includes activity modification, targeted physical therapy, and short-term pain control (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or naproxen; muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine). Improvement is usually seen within 2–6 weeks, and costs typically range from $300 to $1,500 for initial care ⧉.

For persistent or severe cases, interventional options may be considered. Epidural steroid injections and nerve blocks can reduce inflammation and pain (methylprednisolone, triamcinolone injections), with variable effectiveness. Surgery is reserved for clearly defined structural problems and represents less than 5% of lower back pain cases in the U.S.

Real Case

A 52-year-old male from Ohio developed lower back pain after months of desk work and minimal physical activity. Initially dismissed as muscle strain, the pain began radiating into his left leg with numbness. MRI revealed a lumbar disc herniation. After structured physical therapy and one epidural injection, symptoms improved significantly within three months, avoiding surgery altogether.

Reyus Mammadli emphasizes that timely evaluation often prevents unnecessary procedures. In his words, early, targeted treatment usually keeps a manageable problem from becoming a long-term headache — or rather, a backache.

Editorial Advice

Lower back pain is common, but it should never be automatically dismissed. Pain that improves steadily with conservative care is usually not dangerous. Pain that lingers, progresses, or comes with neurological or systemic symptoms deserves professional evaluation.

Reyus Mammadli advises patients to pay attention to patterns rather than isolated episodes. Staying active, addressing pain early, and avoiding prolonged self-treatment are practical steps that protect long-term spinal health. When in doubt, it is better to ask one extra question than to ignore a signal the body is clearly sending.

About the Author

Reyus Mammadli is the author of this health blog since 2008. With a background in medical and biotechnical devices, he has over 15 years of experience working with medical literature and expert guidelines from WHO, CDC, Mayo Clinic, and others. His goal is to present clear, accurate health information for everyday readers — not as a substitute for medical advice.